Gentle Reader – Here are a couple of pieces I wrote rapidly and placed on Twitter recently. I have begun work on a book, directed at my fellow citizens, to discuss these issues. read and comment please!

The first part comes from Ms. Chandra, a former pediatric intensive care unit nurse. She spent nearly six years volunteering on board a hospital ship off the coast of West Africa before her son Ethan’s heterotaxy diagnosis unexpectedly brought her family back to life on land in 2014.

=============================================================

She tweeted a picture of her son’s $231,115 hospital bill to show why laws that protect affordable healthcare are so important.

What she didn’t expect: the hate in response.

Ms. Chandra’s post: It was late on a Friday evening when I collected the day’s letters from the mailbox. One of those envelopes held a medical bill for my 3-year-old son; I’d moved it to the bottom of the pile because I wanted to work up to opening it, but when the ads for roofing companies and oil changes were taken care of, there was nothing else left. I took a deep breath and pulled the sheets of paper from the envelope, scanning them quickly, past line after line of impossibly large numbers, until I found the simple statement, printed in bold letters: PLEASE PAY THIS AMOUNT: $500.

I burst out laughing with the sheer relief of it all. Thank goodness for insurance. I pulled up my calculator and started adding numbers. My children slept upstairs while the tally mounted, and when I got to the end I smiled wryly. $231,115, give or take a dollar or two. The price of a four-chambered heart.

Not all hearts are this expensive, but my son, Ethan, was born with heterotaxy syndrome, a rare condition that can cause any of the internal organs to be malformed, misplaced, multiplied, or missing altogether. Ethan’s insides are a math all their own: two left lungs, five spleens, and nine congenital heart defects. It was his heart that had brought him to the operating room to have his chest opened four times in his short life, and the bill I was holding was for the latest of these surgeries.

I snapped a picture of the bill and opened Twitter on my phone, absentmindedly imagining that someone might be interested in knowing why we medical mamas care so much about laws that ensure our access to affordable health care, why Obamacare has been a lifeline to our children, banning lifetime limits and ensuring that no one would deny them coverage simply because they’d been born with preexisting conditions like heterotaxy. Maybe someone would listen when I explained how terrified I was now that these protections were under siege due to the Trumpcare bill that stood before the Senate.

The tweets came easily; I’ve always been an external processor. I told our story the same way I always do, softening the hard edges of Ethan’s struggle with photos of the tender-hearted little boy who’s fought so hard to make it this far. I wrote about his medical team, about the surgeries and procedures and medications that he will rely on for the rest of his life, and also I wrote about his love for sticks and fireflies and his mama. I begged the people in power to look him in his big brown eyes and tell him to his face that his life was too expensive to be worth saving.

And then I put down my phone and went to sleep, never expecting to find out that the whole world was listening. The days to come would introduce me to the darkness lurking in the savage corners of the internet, and to the promise it holds for families like mine who so desperately need to find community.

“That thread of yours really took off!”

The morning after I sent the tweets, I was at the market with my kids, choosing between scones and muffins, when a friend texted me: “That thread of yours really took off!”

I opened my phone, and instead of the usual 10 or so likes, I found my mentions and messages overrun. There were journalists reaching out to me, verified accounts with millions of followers retweeting me, and a few very angry men telling me that I shouldn’t steal from them, that my child was better off dead, that I should have let him just succumb to natural selection.

It was jarring. One minute I was picking out peaches, and the next I was on the phone with a writer from BuzzFeed while my kids ran around in the grass, totally unaware that our story was capturing the attention of the world for a brief, viral window.

At first, the comments were almost entirely supportive. With the exception of the guy who thought that Ethan should have been more personally responsible (in utero, I guess, although I’ve never been sure how best to explain that concept to an 8-week-old fetus), the vast majority of people were either in shock at just how high the lines on the bill had added up or else they were staunchly on our side. People were ready to fight for a kid they’d never met, and they were sharing their stories with me in the hopes that I’d fight for their children too.

But as more and more people saw the original tweet, the tide seemed to shift. I was still seeing lots of people on our side, but as articles were churned out and shared, it was clear that people weren’t reading much past the headlines. They came at me swinging, picking fights I’d never asked for. They called me ungrateful, a thief, a lazy mooch, an attention whore.

The attacks became increasingly personal and increasingly violent. Strangers were telling me it would have been cheaper to make a new kid, as if anyone in the history of the world could ever replace this bright light of mine, the boy who loves animals and can’t keep himself from kissing babies and always wants to sleep with one arm wrapped around my neck.

I was offered a .22 bullet, although I’m still not sure whom he meant it for, me or my child. One man took me up on the challenge I’d posed in the thread and declared that my son just wasn’t worth keeping alive anymore. There was even a percentage of the comments dedicated to the belief that I was a foreigner or, worse, a terrorist, which is when I started asking news outlets to use my full name: Alison, not Ali, since people seemed unable to believe that I was, in fact, a white chick from New Jersey.

The worst were the ones who attacked on the genetic front. Heterotaxy has no known cause, but in our case it was due to a genetic glitch, a previously unknown fault in the code of my own humanity that I passed down to my son. I don’t think I’ll ever come to terms with the fact that it was me who slipped the poison into his DNA, with knowing that his children (if he ever has them) will stand in front of this same 50-50 firing squad. It’s been my own private heartbreak. Now strangers were tearing barely healed scabs off those old wounds and I was running out of hands to stanch the bleeding.

At first I tried to keep up with the flood and even attempted to reason with some of the haters, but I realized quickly that it was useless, and not just because of the sheer number of comments. It was because no one was listening. No one seemed willing to stop shouting long enough to realize that there was a real person on the other side of the screen, a mother who’s seen her baby go through hell and come out the other side four times now and who just wants him to have a shot at going to kindergarten too.

It was eye-opening to see just how low our discourse has sunk, to be forced to acknowledge that what passes for debate in the age of the internet is often nothing more than spewing venom at the other side. How are we ever supposed to find a solution that’s better than either Trumpcare or Obamacare if we can’t even shut up long enough to recognize the humanity in the people on the other side of the debate?

I hope our story reminds people that anyone could be just one diagnosis away from medical bankruptcy

And then a message from another family of a medically fragile child showed up in my inbox. It wasn’t the first, by any means, but this one was special. It was a mother who had never gotten a proper diagnosis for her son, but after reading our story and doing some research, she’d connected the dots; her son has heterotaxy. She finally had a name for the specter that stalked him, and with that, she could find a community and support as she advocated for her child.

It was like the sunrise after an endless night. My poor, beleaguered heart had been drowning in the fetid pool of the worst the internet has to offer, and suddenly I had been thrown a lifeline. My focus narrowed back to what was important: my son, and the kids like him all across the country, the ones quietly living out their stories every single day with no fanfare and no media attention.

It wasn’t important anymore that bitter internet trolls were calling me a manipulative money-grubbing ingrate. It didn’t matter that there were people fighting with each other and spouting conspiracy theories and competing to say the worst things they could fit into 140 characters in my Twitter mentions. There was a mama out there whose life would never be the same.

I got more messages after that one, people sharing their journeys with heterotaxy, asking to be connected to our groups, wondering whether I could explain more about it. (The answer to that last one is yes, always yes.) I found articles from countries around the world, saw this rare and, until now, unknown disorder translated into languages that spanned the globe, and I realized that all of this was going to have an effect I couldn’t have predicted.

The first time I heard the word “heterotaxy,” it was with my world crumbling underneath me and nothing to hold on to. I Googled it and found only depressing statistics and horror stories. It wasn’t until another mother reached out to me with photos of her son, covered head to toe in mud and grinning, that I finally allowed myself to hope that my boy might have a life beyond hospital walls and heartbreak.

And now the whole world has heard. Now they know that heterotaxy can mean hospitals and surgeries and a lifelong fight, but if another mama somewhere down the road stumbles out of that appointment, broken-hearted and bleary-eyed, maybe she’ll remember the time she saw a little boy named Ethan blowing raspberries on her TV. Maybe she’ll Google heterotaxy and, sandwiched between the black-and-white statistics, she’ll find a boy who sleeps with a stuffed moose (and 15 other animals) and who, thanks to one rather well-known hospital bill, hikes through the woods on sturdy legs, a whole heart instead of the half he was born with beating bravely beneath the scar running the length of this chest.

And the other mamas? The ones who aren’t like me, who haven’t become the “other people,” the ones who bad things happen to? I hope they heard me when I said I want to fight for something better for all of us, for those of us whose children rely on the protections afforded by the current laws and for those of us who are struggling under the system as it stands now.

Some of those people will have heard our story and imagined themselves in our place, maybe for the first time. They will have realized that tragedy does not discriminate, that anyone could be just one diagnosis or one accident away from medical bankruptcy, and that I’m speaking out because I care about my kids but I care about yours too. Maybe this will be the thing that finally gets us to join hands across the political divide and aim our passion away from strangers on the internet and toward the people who are responsible for the laws that affect us all.

And that’s priceless.

============================================

My Response to her: Ms. Chandra – your son is why, since before I became a physician, I’ve believed in and supported a single payer health system.

And still do.

The ACA (Affordable Care Act, “ObamaCare”) was just a good first step; we need to do more. Trump’s “health plan” is more of his abuse.

I am pleased your son is better.

But what, briefly, do we need to be thinking about? Medicare for All (MFA) only resolves one piece of our healthcare disaster: Access. Yes, it’s an important piece but it’s not enough.

If everyone in our country has access to the healthcare system we presently utilize, and if we – all of us, health workers and citizens – continue to (mis) manage the healthcare system as we presently do, we’re in for a fiscal and political disaster. We will break the bank and the right-wing will use quality, safety and financial issues to “prove” that MFA was a boondoggle, that all we have to do is privatize. That would be a shirtless disaster.

We spend about $3.5 trillion now with significant numbers of us – about 23 million – uninsured, and another 20 million or so underinsured. Our total spending on healthcare is the highest in the industrialised world. Our outcomes are some of the worst in the industrialized world. In 2014, we were the worst performing health system in the industrialzed world (Figure [Davis, et al. The Commonwealth Fund, 2014]).

If all we change is access we go broke; look at the health expenditures per capita on the figure. We need to do more.

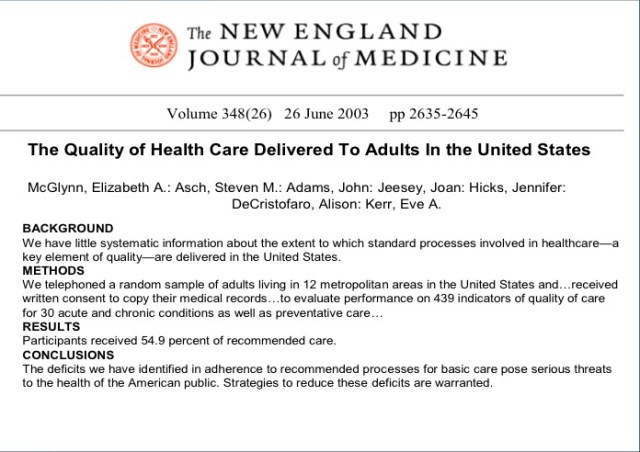

Our focus would be/should be firstly on prevention – the hard stuff!! – including exercise, diet, and time to deal with both. When treatment is needed it must be high quality, safe and evidence based. If no evidence exists academic medical centers do research. We will eliminate the 30% to 50% in the health system that is waste (see Elizabeth McGlynn’s article in the New England J Med 2003). In a $3.5 trillion health system that’s a lot of cash that can be used to cover the costs of the uncovered.

We negotiate drug prices and, by cutting out much of the for-profit insurance companies and their expensive products, we eliminate their overhead of up to 30% (S. Woolandler, New Engl J Med 2003). MFA would cover everything , no supplemental insurance would be needed. The private, for profit insurance companies could sell insurance products covering, for example, elective plastic surgery procedures. So there would still be some small role for private insurance.

We’d have to have a national discussion on salaries for hospital administrators and physicians. Is ANY administrator worth $5 million/year? NO! It would be a challenging discussion, but one that is needed. We would have to have national discussions about birth control, death and dying and so forth.

Something on the order of 90 of our fellow citizens – the sons and daughters of people we know – die daily from drug overdose. This is a medical problem – addiction – not a legal or moral one. We must keep our addicted citizens alive long enough to help them get off IV drugs: Clean needles & syringes; Clean, known drug; Safe-places for injection. These will drastically decrease and possibly prevent overdose deaths. Further, clean needles and syringes will prevent Hepatitis B and C Virus (HBV, HCV) transmission, HIV, and infectious endocarditis (IE). Yes, it will be hard. Yes, some will argue that we are encouraging drug use, even though we are not and there is no evidence to suggest we are. It is still a challenge, but these are our brothers and sisters.

We can no longer simply deny discussion of these and other issues because a small portion of our population finds them distasteful. We must become a health system that’s responsive to our people. We will need to root out all the ways that we see our fellow humans as “other”: sexism, racism, homophobia and so forth. If we do all this…….We have a chance.

None of the above is theoretical, this is entirely doable if we desire. What we lack – at present – is serious and responsive (to us, not billionaires and corporations) leadership.

Oh yes, one more thing.

If we don’t get control of climate change, none of this will matter. We will live in a dystopic, violent world of all-against-all.

Yes, I’m calling BS on the Rs in power.

You must be logged in to post a comment.